(artikkeli englanniksi)

1. Introduction

I had the pleasure of attending a bunraku play when I was living in Osaka in 2008. The experience was unforgettable as my interests in Japan are mostly about the history and the traditional culture. Lately, bunraku has been falling into rough times with only a few puppeteer troupes and the low attendance compared to the golden age of bunraku. It would be a great shame to see this art for disappear.

1.1. History

Puppetry has deep roots in Japan. In the ancient times, puppets were used to impersonate the deceased during ceremonies (Hays, 2014). Later on, during the Heian period, Chinese puppet performing arts had a big impact on the puppetry in Japan. During this time, a travelling street entertainers, called kugutsumawashi, started to emerge going from door-to-door and using puppets to tell stories (Hays, 2014; Encyclopedia Britannica, 2017). These puppeteers were especially influential on the island of Awaji and Nishinomiya near Kobe city.

During the 16th century, the puppetry was combined with the art of chanting storytelling, called joruri. It consists of a storyteller and a musician originally playing a biwa lute. Later the biwa was replaced by a shamisen and combined with the puppeteer troupe, formed the art of ningyo jojuri, the contemporary name of bunraku as we know today (Hays, 2014).

In the 17th century, saw the golden age of bunraku and its development into current form. The puppeteers became visible as well as the narrator and the shamisen player (Skipitares, 2004). The main puppets were operated by a three puppeteers. Bunraku flourished in the city of Osaka, mostly thanks to talented playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon and a powerful chanter / narrator Takemoto Gidayu (Johnson, 1995; Hays, 2014; Joji, 2014). Chikamatsu went on to write more than 100 plays for bunraku including the scandalous “The love suicides at Sonezaki”, which was based on true events that happened only a few weeks earlier (Johnson, 1995; Encyclopedia Britannica, 2017).

The name, bunraku, was given to the art form by Masai Kahei, who was known with a stage name of Uemura Bunrakuken (Hays, 2014). He founded a puppet theater in Osaka in 1805. Due to most other puppeteer troupes being disappeared before that, his name and Osaka became strongly linked to ningyo jojuri.

1.2. The basics of bunraku

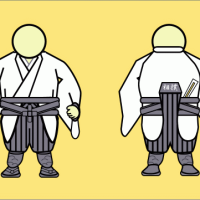

The main element of bunraku is the puppets and the puppeteers operating them. The main character puppets usually have three operators (JNTO, 2017). One of them, called omozukai, controls the head and the expressions as well as the right hand. The other puppeteers are called hidarizukai and ashizukai, who control the left hand and the legs, respectively. Nowadays, the omozukai may be unhooded, while the other puppeteers wear black clothes and a hood in front of their faces (JNTO, 2017). Interestingly, no effort is done to conceal the fact that the puppeteers control the puppets, which is a drastic contrast with western puppet theater (Skipitares, 2004). The puppets themselves are complex. Especially the heads have several moving parts to express different emotions (Hays, 2014). The size of the puppets are about half or 2/3 of a normal human.

The second important feature of bunraku is the narrator, tayu in Japanese. While the puppeteers remain silent, the tayu chants or sings the story giving a voice to all the characters in the play. By the side of tayu, sits a shamisen player who provides the rhythmical background music as well as interprets possible sound effects (Hays, 2014). The skill of the narrator is held in high regard, but the star of the show may be considered to be the play script itself. It is fairly common for the actors in kabuki to interpret the source material as they please, but in kabuki the play almost always performed as the author has written it. The respect towards the source material is evident with the script being visible in front of the tayu at all times and the narrator even bows to the written script at the start of the play (Hays, 2014).

Bunraku is quite slow paced theater, much like noh theater too. The play types are divided generally to historical plays, or jidaimono, and domestic plays, or sewamono. Chikamatsu Monzaemon was a specialist of the sewamono plays of the common people, which helped to popularize the bunraku among the populace (Hays, 2014). Themes of social obligation, personal longings, passions and emotions were common themes in bunraku plays. Other popular topic was suicide. “Love Suicides at Sonezaki” was very popular story, which caused problems for the authorities, as people mimicked the events by killing themselves too. Eventually the play was banned for a while (Hays, 2014; Japan Zone, 2017).

1.3. Decline in popularity

The slow popularity of bunraku started as early as the end of 18th century. This was due to deaths of few very popular puppeteers, authors and narrators (Johnson, 1995). Especially the lack of talented play wrights meant that older plays were recycled without high quality current plays for the contemporary audience. At the end of the Meiji period, only few puppeteer troupes were remaining concentrating in Osaka and around Kansai area.

The Bunrakuza Theater in Osaka founded by Uemura Bunrakuken was destroyed during WW2 (Joji, 2014). It was built again in 1946, but later disagreements within the theater group caused a split into two factions. In 1963 the groups were united as one, and in 1966 National Theater in Tokyo became a permanent home for bunraku plays thus keeping the tradition alive (Johnson, 1995; Joji, 2014; Encyclopedia Britannica, 2017). Finally, in 1984 bunraku returned to its origins to Osaka into the newly established National Bunraku Theatre. Even though the art form has since been declared as an important intangible cultural property by the government (1995) and as intangible cultural heritage of humanity by UNESCO (2003), the attendance in plays has been declining (Joji, 2014). The audiences are only about 1/10 of the popularity of kabuki and because of that the funding for the bunraku in Osaka was cut by 7.3 million yen in 2014 (Joji, 2014).

1.4. Question about the survival of the art

In addition to the decline in popularity, the lack of performers and stage staff is threatening the continuation of bunraku. All of the key roles in bunraku require decades of apprenticeship in order to become a true professional. Becoming the omozukai, skillful tayu, and even making the puppets and costumes require years and years of practice (Johnson, 1995; Joji, 2014; Japan Zone, 2017). This kind of career path undoubtedly doesn’t appeal the modern young people, especially because the apprenticeships are quite poorly payed leading into financial hardships (Hays, 2014).

2. Discussion

In this paper, the efforts to bring back the popularity of bunraku is discussed. The glimpses of hope that are already present, the work for attracting wider audience and speculation about future prospects are elucidated.

2.1. Bringing bunraku back to the masses

The budget cuts in Osaka prompted the theater to take a new approach in promotion of the plays. Traditionally the role of individual performers was downplayed and group effort was emphasized. In 2012 summer season, the performers tried to create a fan base by individual promotion (Hays, 2014). The number of visitors rose by 40% compared to the previous year. Encouraged by the results, a special event featuring five young performers was arranged and the promising new stars of bunraku were heavily promoted (Hays, 2014). This method may be very successful in simulating the strong idol culture in Japan and activating younger generations to try out the puppet theater.

The melancholic and sad stories of the traditional bunraku may not suit the tastes of the modern Japanese people. For example, “Love Suicides at Sonezaki” goes through many unfortunate events and finally culminating in the death of the main characters. One modern interpretation has turned the play around making it into a comedy (Otake, 2013). Koki Mitani, a comedy writer, has made a comical sequel to the famous play with a name of “Much Ado about Love Suicides”. The new play starts at the end of the original and alters it so that the double suicide is prevented by a middle-aged man (Otake, 2013). This kind of fresh look and plays void of the stiffness and elitism of the traditional theater may entice younger audiences. Maybe they grow appreciative to the skill of the performers and striking visuals, thus may in the end go to see even the traditional bunraku performances.

Some of the plays have been shown as a video broadcast, in addition to the live performance, in order to gain larger audiences (Joji, 2014). Also, more family friendly plays have been incorporated into the repertoire. The traditional bunraku plays are based on noh or the subjects are very serious, like suicide. In contrast, western puppet theater has a long history of catering to children as the target audience. Making children familiar with the art form from the young age may be the key in cultivating the future generations of spectators as well as bunraku performers and artisans.

One of the most ambitious efforts to revitalize bunraku is by the Nippon Foundation. In 2015, the foundation launched the Nippon Bunraku Project (Nippon.com, 2017). The theme is to bring the bunraku out of the traditional theaters in Osaka and Tokyo and have performances in unexpected locations. So far, plays have been shown in Roppongi Hills Tokyo, Naniwanomiya palace ruins Osaka, Sensoji temple Tokyo and Ise shrine (Nippon.com, 2017). Bunraku used to be the theater for the common people, while noh was for the nobility. But today’s bunraku is seen as high culture for older elite. The project aims to make bunraku more casual entertainment. The key is a portable stage that enables outdoor plays for spectators that can eat and drink while enjoying the performances (Nippon.com, 2017). The performances will continue through the 2020 Olympics. Hopefully the masses of Olympic visitors will have time also to experience this side of the Japanese culture and possibly increase the image and popularity of bunraku around the world.

2.2. Pop culture collaborations

The absence of human performers should allow great flexibility and creativity to merge bunraku with modern elements. One effort comes from abroad, instead Japan. Bunraku puppetry has been combined with the famous Disney story, The Lion King, as a Broadway performance (Weber, 2017). Instead of dark clothed puppeteers, single puppet is controlled by one performer in quite colorful outfit. Needless to say, the story is child friendly, bright and relatable for contemporary people.

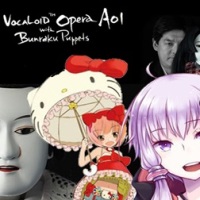

Another interesting collaboration comes from Japan. As bunraku uses puppets to do the task of actors, similarly computer synthesized singer, or vocaloid, can be used instead of an actual human singer. One performance in 2014 combined these two aspects in a show featuring both bunraku puppets and vocaloids, that are used instead of the tayu narrators (Opera Aoi, 2017). Because the music is also played from a computer, the only human element in play is the single bunraku puppet operator. The performance was also shown to an international audience in London.

For lasting popularity, I think that the potential fan base of bunraku has to be acquired as soon as possible. Namely, more plays should be targeted at the children in order to familiarize them with bunraku. Because there are no human actors, no barriers for using popular culture icons like Hello Kitty or Pokemon are present. The variability of the plays could grow as the target audience grows with themes ranging from Anpanman to Kamen Rider and famous manga or anime. This should keep the interest up, and these spectators would even go to see the old traditional plays when their tastes in topics have matured enough.

Furthermore, as shown by the vocaloid example, bunraku might be very suitable to adopt the latest technologies for boosting the appeal. Visual special effects could be used to liven up the stage. One could envision the use of robots to accompany the human operated puppets. Some of these robots could even be in limited control of the audience members bringing a high level of interaction and participation. In my opinion, the children might enjoy this kind of hands on approach greatly and might inspire them to consider a career in bunraku, theater or possibly robotics sciences. Another step further in increasing the visual appeal of bunraku might be the application of augmented reality, or AR. Light weight AR systems, like the Hololens by Microsoft, can offer possibilities that the normal puppet theater can’t provide. Only the imagination of the creators is the limit in considering the possibilities of merging the modern culture and the traditional art of bunraku.

3. Conclusion

Bunraku has significantly fallen in popularity since the heydays of the medieval Japan. This is partly due to structural problems and partly due to the change in image from entertainment for the common people to high culture for the wealthy elite. The answer is in the change of attitude and increasing the appeal for the modern audiences. The traditional plays will still remain even though the art form would evolve to encompass more varied themes and adopt newer technologies. Great efforts have already been done to increase the appeal of bunraku, but a lot is still to be done for the popularity to reach even levels of kabuki plays.

4. References

Encyclopedia Britannica. (2017). Bunraku – Japanese puppet theatre. link

Hays, J. (2014). BUNRAKU, JAPANESE PUPPET THEATER. Facts and details. link

Japan Zone. (2017). Bunraku Puppet Theater. link

JNTO: Japan National Tourism Organization. (2017). Bunraku. link

Johnson, M. (1995). A Brief Introduction to the History of Bunraku. The Puppetry Home Page. link

Joji, H. (2014). The Rich History and Uncertain Future of Bunraku Puppet Theater. Nippon.com link

Nippon.com. (2017). Outdoor Performances Bring Bunraku Back to Its Popular Roots. link

Opera Aoi. (2017). VOCALOID™ Opera AOI with Bunraku Puppets. link

Otake, T. (2013). Koki Mitani adds comedy to bunraku. The Japan Times. Aug 7. link

Skipitares, T. (2004). The Tension of Modern Bunraku. PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art, 26(1), 13-21. link

Weber, K. (2017). Japanese Bunraku Puppets. The world of puppetry. link

Ajankohtainen artikkeli bunrakusta ja jutussa mainitsemastani Nippon Bunraku Projektista: http://www.nippon.com/en/views/b02329/